We're hosting an exhibition of works by Mark Flood from late May through mid June. I've wanted to write something extensive about the show, as I find it very thought provoking. However, this has proven difficult. The show opens onto too many themes and consists of too many elements to address without weeks of consideration. Therefore the notes and images that follow consist of details and summaries. Perhaps they will provide a sense without finality, something utterly contingent upon my own relation to the works after a single week of viewing. This is particularly pertinent in consideration of the images that follow, many of which appear as details which I photographed and do not depict the actual works in their entirety. I have photographed them after my own fashion, as an attempt to understand the exhibition and have often discovered something in the photographs which I had overlooked with my eyes.

There are several elements to the show, which can superficially be described as an installation which features twenty five collage works; a pile of contemporary Hollywood head-shots; a pile of newspapers from September 1921; film projectors of widely various vintages; and decaying front pages of the same newspapers as can be found on the floor, pinned to a large portion of one wall, with headlines pertaining to the arrest of Fatty Arbuckle for manslaughter.

The show is titled ECU, short for Extreme Close Up, a title which best fits the collage works that appear in the exhibition. Various celebrities, both past and present, have received treatment. As you'll see in the images below, these "ECU's" look like they've been through the "ICU", and might have fared better. Their appearances can be quite gruesome. And yes, analogy with the impact of inexpert plastic surgery asserts itself rather openly.

Take for example, this detail from one collage depicting Jimmy Kimmel:

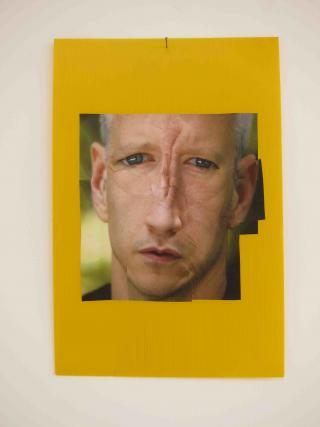

And there's this image of Flood's Anderson Cooper collage, which gives you a better sense of his work and installation strategy, which is decidedly rough, a single nail through irregularly shaped corrugated plastic sign board:

As mentioned previously, Flood has introduced several film projectors from his personal collection, some quite old, to the room and added two that we had lying around the bookstore office. The table and projector which appeared in our recent Rosa Barba exhibition reappear here, in a significantly altered context. In fact, the 16 mm film projectors huddled by the fire exit in the back of the gallery seem to pose the question: what's the point in referring to "film" at this point in history?

(I am reminded of the following story: in looking around the States to find a looping device for Rosa Barba's recent 16 mm installation, one of the people I spoke with, who worked for a prominent rental agency, told me to "move on" and "get over it".)

From an installation standpoint, the room is divided into two parts. The larger part of the room is dedicated to contemporary film culture and a smaller, though still significant portion to silent film. The division invites comparisons. On one wall, a collage featuring Lindsay Lohan neighbors one of silent film star Wallace Reid. Addiction features prominently in both of their biographies. Questioning the durability of celebrity is another consequence of the division. Once widely recognized, widely loved, and widely criticized, I needed Wikipedia to tell me who Reid was. And yet, I realize, he lived quite recently. It seems almost ridiculous to write, the power of celebrity in any moment is so strong, but Reid's story argues: few people will recognize Brad Pitt in one hundred years.

Lohan fans will be happy to know that though she appears in two collages, she escapes treatment in both. In fact, in the collage I've just mentioned, one based on a photo in which Lohan is being questioned by the police, it's the officers whose faces have been altered.

Contrasting with the maimed faces on the walls, Flood has made a pile of recent head shots at the contemporary end of the gallery. Small post-its and other items attached to the photos address sitcom appearances and minor speaking roles, but fundamentally: the hundred or so people pictured are unknowns.

If not for the humiliation of the situation, being one of many faces scattered about the floor, you might consider these people lucky, having eluded the knife. However, upon reading any of the notations made to the photos, you think again. "Great emotional range". Apparently no one escapes the horrors of celebrity, not even the unknowns.

At the other end of the gallery, tacked to the wall, Flood has placed a collection of newspaper headlines from late 1921 announcing the arrest of silent film comedian Fatty Arbuckle, charged with manslaughter in the death of actress Virginia Rappe. The interiors of the newspapers, the less-thrilling parts, appear in a pile on the floor.

In the story that is pictured below, one of those that appears on the wall, Arbuckle's mother is quoted as saying, "Too much money went to his head."

What do we make of the grinning Arbuckle, posed here not as a criminal, but as a comedian? In fact, the word "Triangle", which follows the comma after his name, refers to the famous film production company and Fatty's employer. What do we make of the fact that the same publicity photo is used for both purposes, film promotion and arrest? And, what does that mean, "too much money went to his head"? Are we being asked to believe the outcome of too much money is manslaughter?

One of the more surprising things I read among the hundreds of browning pages littered about the floor was this little piece advertising a film to feature none other than Wallace Reid.